|

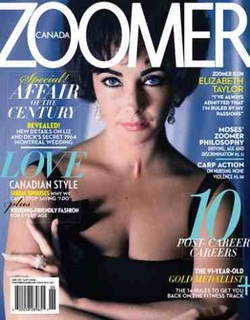

When Liz and Dick Got Married

|

They called it ‘the marriage of the century’ and we were enthralled

It was the winter of 1964 and Toronto was strangely giddy about something other than hockey. The Maple Leafs seemed primed to win a third straight Stanley Cup victory that season but the city instead was in the thrall of Hollywood glamour. Movie star sightings in Toronto in the early ‘60s were about as common as palm trees on Yonge Street, and they could cause the populace to become a little overexcited. When Italian screen goddess Gina Lollobrigida had relocated to Toronto with her family in 1960, their rented house soon became so thronged by gawkers that La Lolla had quickly fled back to the Appian Way.

Now another celebrity siege was underway but this time it was for a star duo called THE MOST FAMOUS COUPLE ON EARTH. Elizabeth Taylor’s steamy, adulterous affair with Richard Burton, begun on the set of the costly film epic Cleopatra in 1962, had propelled them into a kind of supernova of stardom. Adultery could be a celebrity career-killer—NBC had canceled singer Eddie Fisher’s TV show in 1959 after he had left the pert Debbie Reynolds for ‘homewrecker’ Elizabeth Taylor. But a few years later, scandal only seemed to supercharge the phenomenon known as Liz-and-Dick, a sign that perhaps ‘the swinging 60s’ were indeed underway.

“Ghastly crowds of morons besiege the hotel where Burton and Taylor are staying,” wrote John Gielgud in a letter to his partner on February 2, 1964, “every drink and conversation they have is paragraphed and reported. It really must be hell for them….” Sir John was in Toronto to direct a new production of Hamlet at the O’Keefe Centre (now the Sony Centre) in which Burton would star in the role that Gielgud himself had interpreted so memorably years before.

Fearing media mania when the famous pair arrived in Toronto on January 29, Hugh Walker, the tall, courtly Scot who managed the O’Keefe Centre, had made plans to meet them at Malton Airport. “My fears were well founded,” he later wrote. “There were about 3,000 people including reporters and photographers waiting in the airport terminal.” Walker managed to escort the two stars through a side door into customs and then to a limousine. They were both grateful for this reception since there had been near-riots when they had left Los Angeles that morning and again during a stopover in Chicago. Burton had requested a suite at the King Edward Hotel, since he had stayed there during the run of Camelot, the musical that had opened the O’Keefe Centre four years earlier. Walker recalled that when the limo arrived at the King Eddy, “it was a grim business getting them through the crowds to the Vice-Regal Suite.” One picketer on the sidewalk carried a sign that read, ‘Drink Not The Wine of Adultery.’

With armed guards posted at the door, the couple then became virtual prisoners in their eighth-floor suite. Elizabeth took to walking her two poodles on the roof to avoid running the gauntlet at the hotel entrances. She only attended rehearsals twice and sat and listened attentively since classical theatre was new to her. “She steeped herself in the play and its various interpretations,” remembered actor Richard L. Sterne who had a small role in the production. He also recalled how “awesomely beautiful” Taylor was. “I can still see her coming into the rehearsal hall for the first time…dressed in a purple pantsuit. You couldn’t miss those violet eyes.”

Burton’s famously mellifluous voice and his “magnetic aura” were equally unforgettable to Sterne as was the amount of alcohol the star could consume without it seeming to affect his performance. Gielgud was more dubious about this. “Richard …is full of charm and quick to take criticism and advice,” he wrote to playwright Emlyn Williams, “but he does put away the drink, and looks terribly coarse and heavy—gets muddled and fluffy and then loses all his nimbleness and attack.”

According to Sterne, “Richard adored Sir John…we all did,” but he also noted that rehearsals often became “a brilliant, butterfly-brained lecture by Gielgud.” During their enforced evening seclusion at the King Eddy, Richard confided to Elizabeth his discomfort with Gielgud’s direction and his worries about the demands of the role. Laurence Olivier had once sent a telegram to Burton, asking, “Do you want to be a great actor or a household word?” to which he had famously replied, “Both!” But now after a decade mainly devoted to movies, Burton keenly felt the pressure to prove that he could indeed be both.

Canadian actor Hume Cronyn, who was a brilliant Polonius in the play, was also the cast’s “steadier of nerves,” according to Hugh Walker. Noting the strain that the famous couple was under, Cronyn approached Walker in early February about finding a place for them to have a weekend’s escape. Walker contacted Louanne Cassels, wife of Tony Cassels, the board chair of the National Ballet, whom he knew had a family compound on Lake Simcoe. Louanne was busily planning a gala performance of Hamlet as a fundraiser for the ballet and quickly agreed to provide a country retreat for the famous pair. After Saturday night’s preview performance on February 15, the couple’s black limo was kept idling at the stage door while they made a getaway in a car driven by Hume Cronyn’s niece. They drove to Cronyn’s apartment, changed cars again, and were then driven north by Louanne and Tony Cassels.

Taylor and Burton were left to themselves in the cottage and the next day they took a walk on the frozen lake. “I remember my mother thinking it was all quite funny,” recalls Doug Woods, a

Cassels nephew who was then sixteen, “here they were trying to be incognito and she's walking on the lake in a snow-leopard coat!” The Cassells-Woods clan was staying next door and that evening Burton and Taylor were invited in for drinks. “The kids were banished to another room,” remembers Woods, “but we were brought in to be introduced. Burton was a bear, a big guy, but he had an animal magnetism about him that was palpable. She was quite petite, much shorter than I imagined, and with a very prominent bosom ––something you notice at sixteen. She struck me as very nice, very quiet, a lot less gregarious than he was.”

Doug’s seven-year-old sister, Nancy, didn’t know who Elizabeth Taylor was but she recognized Burton’s voice from the family’s LP recording of Camelot. She later put it on and Burton sat her on his knee and sang along with it. “Our parents swore us to secrecy about the visit,” Woods remembers, “and we never talked about it – not for years.” Dropping a name like Liz Taylor would have earned big status at Upper Canada College, the posh boy’s school the three Woods brothers attended, but none of them ever claimed bragging rights. Another school secret was the stunt that the senior class was planning for the premiere of Hamlet.

“As soon as we heard that our student tickets were for the opening night, we knew we had to do something,” UCC ‘old boy’ Alan ‘Monk’ Marr, remembers. “I was the class cutup, known for doing impressions of the teachers, and I had a garage band called ‘Monk Marr and the Clergy Reserves’ that played at school dances. But Scott Hall and Mike Royce, both prominent lawyers today, were the main instigators and we planned the whole thing like a military campaign. The whole class pooled money to rent a big black limo from a Forest Hill livery service. A guy named Mark Phillips, (now a CBS newsman), had a big Harley so we got him to be the motorcycle escort in a UCC cadet battalion uniform.”

On the opening night, February 26, with the world’s press gathered at the O’Keefe Centre, groups of Marr’s classmates were busily working up the crowd outside. “Is it true Monk Marr is coming?” they asked aloud. To anyone who looked puzzled they’d add, “He’s a famous satirist and rock singer from New York.” When the limo approached, Rick Bell, (later a keyboardist for Janis Joplin and The Band), shouted out, “ It’s him, it’s him! It’s Monk Marr!” As the big-finned Cadillac pulled up, its little flags marked MM flapping. Mark Phillips revved his Harley and pandemonium erupted. “We want Monk Marr!” the crowd chanted while flashbulbs popped. In sunglasses and a red tuxedo with black satin lapels, Alan Marr stepped out of the car while two burly school friends, one with a walkie talkie, cleared the way for him through the crowd. “When the frenzy died down,” Marr remembers, “we had to make our way up the escalators to the cheapest seats in the house”

Following this kind of excitement, the play itself could only be anticlimactic, and in reviewing it for the UCC school magazine, John Bosley, (a future MP and House Speaker), wrote that “it tended to drag and be boring in parts.” Bosley didn’t care for the bare staging with only rehearsal clothes as costumes, a view shared by most of the Toronto critics, accustomed to splashier Shakespeare at Ontario’s Stratford Festival. Nathan Cohen in the Star called the production “ an unmitigated disaster” though the Telegram called Burton’s performance “magnificent.” Telegram columnist Mackenzie Porter soon unmasked the Monk Marr caper but Paris-Match reported breathlessly on ‘L’arrivée de Monk Marr’.

The reviews did not dampen the spirits of the cast or its star and the next night Elizabeth Taylor’s thirty-second birthday was celebrated backstage at the O’Keefe with the actors and crew. She cut the large cake with a fencing sword and in the words of Richard Sterne, “couldn’t have been lovelier.” As a birthday present Burton gave her a stunning $150,000 Bulgari emerald-and-diamond necklace. The following week she received something just as welcome—a Mexican divorce from her fourth husband, Eddie Fisher. Since Burton had divorced his first wife, the Welsh actress Sybil Williams, in 1963, the couple were now free to marry. But not in Ontario ––Mexican divorces were not recognized by the province. The couple’s lawyer soon discovered that they could be married in Quebec and so on Sunday morning March 15, Burton and Taylor and a small entourage of nine that included their publicist, lawyer, tax specialist, and Burton’s dresser, boarded a private Vickers Viscount for Montreal. Three limousines were waiting at Dorval Airport to whisk them to the Ritz-Carlton where Richard and Elizabeth registered as ‘Mr and Mrs Smith.’ They were escorted to the Royal Suite by the manager and soon two crates of champagne and two dozen champagne glasses were wheeled in.

Civil marriage did not exist in Quebec at the time, and finding a minister to conduct the service had not been easy. But Reverend Leonard Mason of a Unitarian church just across Sherbrooke Street had agreed to preside. Elizabeth retired to a bedroom and eventually reappeared in a yellow chiffon dress by Irene Sharaff who had designed her costumes for Cleopatra. In her coiffed hair were hyacinths and lily-of-the-valley and she wore her birthday Bulgari necklace along with matching earrings that were Richard’s wedding gift. The service was brief and afterward only a short statement from Richard was issued to the press: “Elizabeth Burton and I are very happy.”

After the reception ended at around six, the newlyweds dined alone in the suite. The hotel had been sealed off by security but a young Gazette reporter named David Tafller managed to climb up the service stairs. “I peeked out from the service staircase, saw nobody on guard at Room 810, and walked down the corridor,” Tafler later wrote. “From the room I could hear either a radio or a TV set blaring. I took a deep breath, and knocked. The latch was pulled, the knob turned, and there was Burton. He was in his bathrobe and didn't look anything like he did in Cleopatra. He just looked like an ordinary man of 40 or so, maybe a little tired, and certainly not in the mood for a conversation with a newsman. "Excuse me," I began. And that was all. He slammed the door and I could hear the lock fall into place.”

By morning, a crowd had gathered in front of the Ritz and plans were made for the newlyweds to leave by a back door. But Burton said, “These people came expressly to see us,” and led Elizabeth out the front door to cheers and some shouted queries from the press. They were back in Toronto for Tuesday night’s performance at the O’Keefe Centre which Elizabeth watched from the wings. After the curtain call, Richard held out his hand and she joined him onstage. “I say we shall have no more marriages,” he said, quoting a line from Hamlet to Ophelia. The audience stood and cheered.

There were to be more marriages, of course—three more for each of them. One, in 1975, would be a remarriage but it would last only five months since Burton soon resumed the heavy drinking that had led to their break-up in 1974. In the recently-published book, The Richard Burton Diaries, many of the daily entries in his mid-70s journals consist of just one word: “Booze.” Yet when writing during the early years of their marriage, Burton’s charm and eloquence are on full display. In November of 1968 he writes:

I've been inordinately lucky all my life but the greatest luck of all has been Elizabeth. She's turned me into a moral man but not a prig, she's a wildly exciting lover-mistress, she's shy and witty, she's nobody's fool, she's a brilliant actress, she's beautiful beyond the dreams of pornography, she can be arrogant and wilful, she's clement and loving, she can tolerate my impossibilities and my drunkenness, she's an ache in the stomach when I'm away from her, and she loves me!

I'll love her till I die.

It was the winter of 1964 and Toronto was strangely giddy about something other than hockey. The Maple Leafs seemed primed to win a third straight Stanley Cup victory that season but the city instead was in the thrall of Hollywood glamour. Movie star sightings in Toronto in the early ‘60s were about as common as palm trees on Yonge Street, and they could cause the populace to become a little overexcited. When Italian screen goddess Gina Lollobrigida had relocated to Toronto with her family in 1960, their rented house soon became so thronged by gawkers that La Lolla had quickly fled back to the Appian Way.

Now another celebrity siege was underway but this time it was for a star duo called THE MOST FAMOUS COUPLE ON EARTH. Elizabeth Taylor’s steamy, adulterous affair with Richard Burton, begun on the set of the costly film epic Cleopatra in 1962, had propelled them into a kind of supernova of stardom. Adultery could be a celebrity career-killer—NBC had canceled singer Eddie Fisher’s TV show in 1959 after he had left the pert Debbie Reynolds for ‘homewrecker’ Elizabeth Taylor. But a few years later, scandal only seemed to supercharge the phenomenon known as Liz-and-Dick, a sign that perhaps ‘the swinging 60s’ were indeed underway.

“Ghastly crowds of morons besiege the hotel where Burton and Taylor are staying,” wrote John Gielgud in a letter to his partner on February 2, 1964, “every drink and conversation they have is paragraphed and reported. It really must be hell for them….” Sir John was in Toronto to direct a new production of Hamlet at the O’Keefe Centre (now the Sony Centre) in which Burton would star in the role that Gielgud himself had interpreted so memorably years before.

Fearing media mania when the famous pair arrived in Toronto on January 29, Hugh Walker, the tall, courtly Scot who managed the O’Keefe Centre, had made plans to meet them at Malton Airport. “My fears were well founded,” he later wrote. “There were about 3,000 people including reporters and photographers waiting in the airport terminal.” Walker managed to escort the two stars through a side door into customs and then to a limousine. They were both grateful for this reception since there had been near-riots when they had left Los Angeles that morning and again during a stopover in Chicago. Burton had requested a suite at the King Edward Hotel, since he had stayed there during the run of Camelot, the musical that had opened the O’Keefe Centre four years earlier. Walker recalled that when the limo arrived at the King Eddy, “it was a grim business getting them through the crowds to the Vice-Regal Suite.” One picketer on the sidewalk carried a sign that read, ‘Drink Not The Wine of Adultery.’

With armed guards posted at the door, the couple then became virtual prisoners in their eighth-floor suite. Elizabeth took to walking her two poodles on the roof to avoid running the gauntlet at the hotel entrances. She only attended rehearsals twice and sat and listened attentively since classical theatre was new to her. “She steeped herself in the play and its various interpretations,” remembered actor Richard L. Sterne who had a small role in the production. He also recalled how “awesomely beautiful” Taylor was. “I can still see her coming into the rehearsal hall for the first time…dressed in a purple pantsuit. You couldn’t miss those violet eyes.”

Burton’s famously mellifluous voice and his “magnetic aura” were equally unforgettable to Sterne as was the amount of alcohol the star could consume without it seeming to affect his performance. Gielgud was more dubious about this. “Richard …is full of charm and quick to take criticism and advice,” he wrote to playwright Emlyn Williams, “but he does put away the drink, and looks terribly coarse and heavy—gets muddled and fluffy and then loses all his nimbleness and attack.”

According to Sterne, “Richard adored Sir John…we all did,” but he also noted that rehearsals often became “a brilliant, butterfly-brained lecture by Gielgud.” During their enforced evening seclusion at the King Eddy, Richard confided to Elizabeth his discomfort with Gielgud’s direction and his worries about the demands of the role. Laurence Olivier had once sent a telegram to Burton, asking, “Do you want to be a great actor or a household word?” to which he had famously replied, “Both!” But now after a decade mainly devoted to movies, Burton keenly felt the pressure to prove that he could indeed be both.

Canadian actor Hume Cronyn, who was a brilliant Polonius in the play, was also the cast’s “steadier of nerves,” according to Hugh Walker. Noting the strain that the famous couple was under, Cronyn approached Walker in early February about finding a place for them to have a weekend’s escape. Walker contacted Louanne Cassels, wife of Tony Cassels, the board chair of the National Ballet, whom he knew had a family compound on Lake Simcoe. Louanne was busily planning a gala performance of Hamlet as a fundraiser for the ballet and quickly agreed to provide a country retreat for the famous pair. After Saturday night’s preview performance on February 15, the couple’s black limo was kept idling at the stage door while they made a getaway in a car driven by Hume Cronyn’s niece. They drove to Cronyn’s apartment, changed cars again, and were then driven north by Louanne and Tony Cassels.

Taylor and Burton were left to themselves in the cottage and the next day they took a walk on the frozen lake. “I remember my mother thinking it was all quite funny,” recalls Doug Woods, a

Cassels nephew who was then sixteen, “here they were trying to be incognito and she's walking on the lake in a snow-leopard coat!” The Cassells-Woods clan was staying next door and that evening Burton and Taylor were invited in for drinks. “The kids were banished to another room,” remembers Woods, “but we were brought in to be introduced. Burton was a bear, a big guy, but he had an animal magnetism about him that was palpable. She was quite petite, much shorter than I imagined, and with a very prominent bosom ––something you notice at sixteen. She struck me as very nice, very quiet, a lot less gregarious than he was.”

Doug’s seven-year-old sister, Nancy, didn’t know who Elizabeth Taylor was but she recognized Burton’s voice from the family’s LP recording of Camelot. She later put it on and Burton sat her on his knee and sang along with it. “Our parents swore us to secrecy about the visit,” Woods remembers, “and we never talked about it – not for years.” Dropping a name like Liz Taylor would have earned big status at Upper Canada College, the posh boy’s school the three Woods brothers attended, but none of them ever claimed bragging rights. Another school secret was the stunt that the senior class was planning for the premiere of Hamlet.

“As soon as we heard that our student tickets were for the opening night, we knew we had to do something,” UCC ‘old boy’ Alan ‘Monk’ Marr, remembers. “I was the class cutup, known for doing impressions of the teachers, and I had a garage band called ‘Monk Marr and the Clergy Reserves’ that played at school dances. But Scott Hall and Mike Royce, both prominent lawyers today, were the main instigators and we planned the whole thing like a military campaign. The whole class pooled money to rent a big black limo from a Forest Hill livery service. A guy named Mark Phillips, (now a CBS newsman), had a big Harley so we got him to be the motorcycle escort in a UCC cadet battalion uniform.”

On the opening night, February 26, with the world’s press gathered at the O’Keefe Centre, groups of Marr’s classmates were busily working up the crowd outside. “Is it true Monk Marr is coming?” they asked aloud. To anyone who looked puzzled they’d add, “He’s a famous satirist and rock singer from New York.” When the limo approached, Rick Bell, (later a keyboardist for Janis Joplin and The Band), shouted out, “ It’s him, it’s him! It’s Monk Marr!” As the big-finned Cadillac pulled up, its little flags marked MM flapping. Mark Phillips revved his Harley and pandemonium erupted. “We want Monk Marr!” the crowd chanted while flashbulbs popped. In sunglasses and a red tuxedo with black satin lapels, Alan Marr stepped out of the car while two burly school friends, one with a walkie talkie, cleared the way for him through the crowd. “When the frenzy died down,” Marr remembers, “we had to make our way up the escalators to the cheapest seats in the house”

Following this kind of excitement, the play itself could only be anticlimactic, and in reviewing it for the UCC school magazine, John Bosley, (a future MP and House Speaker), wrote that “it tended to drag and be boring in parts.” Bosley didn’t care for the bare staging with only rehearsal clothes as costumes, a view shared by most of the Toronto critics, accustomed to splashier Shakespeare at Ontario’s Stratford Festival. Nathan Cohen in the Star called the production “ an unmitigated disaster” though the Telegram called Burton’s performance “magnificent.” Telegram columnist Mackenzie Porter soon unmasked the Monk Marr caper but Paris-Match reported breathlessly on ‘L’arrivée de Monk Marr’.

The reviews did not dampen the spirits of the cast or its star and the next night Elizabeth Taylor’s thirty-second birthday was celebrated backstage at the O’Keefe with the actors and crew. She cut the large cake with a fencing sword and in the words of Richard Sterne, “couldn’t have been lovelier.” As a birthday present Burton gave her a stunning $150,000 Bulgari emerald-and-diamond necklace. The following week she received something just as welcome—a Mexican divorce from her fourth husband, Eddie Fisher. Since Burton had divorced his first wife, the Welsh actress Sybil Williams, in 1963, the couple were now free to marry. But not in Ontario ––Mexican divorces were not recognized by the province. The couple’s lawyer soon discovered that they could be married in Quebec and so on Sunday morning March 15, Burton and Taylor and a small entourage of nine that included their publicist, lawyer, tax specialist, and Burton’s dresser, boarded a private Vickers Viscount for Montreal. Three limousines were waiting at Dorval Airport to whisk them to the Ritz-Carlton where Richard and Elizabeth registered as ‘Mr and Mrs Smith.’ They were escorted to the Royal Suite by the manager and soon two crates of champagne and two dozen champagne glasses were wheeled in.

Civil marriage did not exist in Quebec at the time, and finding a minister to conduct the service had not been easy. But Reverend Leonard Mason of a Unitarian church just across Sherbrooke Street had agreed to preside. Elizabeth retired to a bedroom and eventually reappeared in a yellow chiffon dress by Irene Sharaff who had designed her costumes for Cleopatra. In her coiffed hair were hyacinths and lily-of-the-valley and she wore her birthday Bulgari necklace along with matching earrings that were Richard’s wedding gift. The service was brief and afterward only a short statement from Richard was issued to the press: “Elizabeth Burton and I are very happy.”

After the reception ended at around six, the newlyweds dined alone in the suite. The hotel had been sealed off by security but a young Gazette reporter named David Tafller managed to climb up the service stairs. “I peeked out from the service staircase, saw nobody on guard at Room 810, and walked down the corridor,” Tafler later wrote. “From the room I could hear either a radio or a TV set blaring. I took a deep breath, and knocked. The latch was pulled, the knob turned, and there was Burton. He was in his bathrobe and didn't look anything like he did in Cleopatra. He just looked like an ordinary man of 40 or so, maybe a little tired, and certainly not in the mood for a conversation with a newsman. "Excuse me," I began. And that was all. He slammed the door and I could hear the lock fall into place.”

By morning, a crowd had gathered in front of the Ritz and plans were made for the newlyweds to leave by a back door. But Burton said, “These people came expressly to see us,” and led Elizabeth out the front door to cheers and some shouted queries from the press. They were back in Toronto for Tuesday night’s performance at the O’Keefe Centre which Elizabeth watched from the wings. After the curtain call, Richard held out his hand and she joined him onstage. “I say we shall have no more marriages,” he said, quoting a line from Hamlet to Ophelia. The audience stood and cheered.

There were to be more marriages, of course—three more for each of them. One, in 1975, would be a remarriage but it would last only five months since Burton soon resumed the heavy drinking that had led to their break-up in 1974. In the recently-published book, The Richard Burton Diaries, many of the daily entries in his mid-70s journals consist of just one word: “Booze.” Yet when writing during the early years of their marriage, Burton’s charm and eloquence are on full display. In November of 1968 he writes:

I've been inordinately lucky all my life but the greatest luck of all has been Elizabeth. She's turned me into a moral man but not a prig, she's a wildly exciting lover-mistress, she's shy and witty, she's nobody's fool, she's a brilliant actress, she's beautiful beyond the dreams of pornography, she can be arrogant and wilful, she's clement and loving, she can tolerate my impossibilities and my drunkenness, she's an ache in the stomach when I'm away from her, and she loves me!

I'll love her till I die.